Shreveport citizens are currently caught in the midst of a battle over a tax renewal. Six proposals up for vote this month aim to renew taxes which we have been paying for dcecades to cover a number of expenses for specific needs such as police, fire, service equipment, city employees, parks, and roads. It’s hard to imagine, with the concerns about crime, quality of life, and public infrastructure that anyone would be opposed to such a renewal, but here we are.

There is plenty of information out there as to what each of the tax renewals are for, so I’ll cover that later in the article and try to focus on addressing one question: Why are some Shreveporters opposed to funding solutions to the very problems they find the most serious, namely, crime and infrastructure?

A “New” Tax

Some Shreveporters focus on the idea that, because these taxes were not renewed before expiration last year, these propositions represent “new” taxes. This attachment to technicality requires voters to pretend past laws never existed. Sure, you can choose to look at it this way. If renewed, Shreveport’s taxes will be the same in 2018 as they were in 2017. The word “new” is a purposefully-misleading legalese semantic. No one’s taxes are increasing. Only one of the tax proposals is really “new” (Prop 6) and that’s because it moved from being a constitutionally-protected tax to one that the State of Louisiana now requires us to vote on.

The last two times we renewed the original five propositions we did so after they expired, and the Louisiana Secretary of State approved language for the ballot that reads “Shall the City of Shreveport continue to levy…”, (emphasis mine) which recognizes that it was levied before and, if approved, would continue as it had since these propositions were first introduced in 2003 by then-mayor, Keith Hightower.

This “new tax” perspective is one that’s specifically meant to give ammunition to those who already feel like the total taxes we pay to all the taxing entities are too high. When confronted with the argument that property taxes would be identical to last year, or that the city’s portion of property taxes is actually less than a quarter of the total property taxes we pay, the opposition sometimes shifts to arguments like “taxes could be lower” and “the city isn’t being good stewards of the money“ – both of which are very different arguments which I will address in detail later in this article.

Tax Breakdown: City vs Parish vs Schools vs…

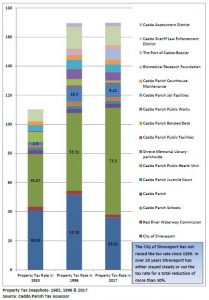

The 2017 property tax millage rate, which includes city, parish, schools, and sheriff taxes, among other smaller taxes, was 164.28 “mills”, which is short for “millage” which means “one part in one thousand”. Of that 164.28 mills, the city only collects 35.81 mills or roughly 22% of your property taxes.

To calculate property tax, the parish tax assessor values a property and the structures on it. For the sake of simplicity, let’s say a residential property and home is valued at $100,000 (the average residential property value in Shreveport is $102,000, so we’re just getting to a clean number here). The property value is then multiplied by 0.1 (10%). The resulting number is known as the “taxable value,” which in our example is $10,000. Then, the millage rate is applied. If the millage rate is 164.28, this means that the $10,000 taxable value is multiplied by 0.16428. From that, we get $1,642.80. Of that, the city takes just $358.10 (the city doesn’t provide for Homestead Exemption, so I’m leaving it out). All the rest of that tax goes to entities like the parish, schools, the port, BRF, Red River Waterway Commission, etc. Click on the chart to enlarge the breakdown.

This means, based on the average residential property value of $102,000, Shreveport property owners pay, on average, $365.26 a year in taxes on their property to the city, or $1 per day per home. That’s not even per person living in the home. The national average is 3 people per home which would mean the taxes paid to the city would be roughly $0.34 per person per day.

Think about all the things these cents per day contribute to: police, fire, trash collection, sewage, roads, sidewalks, administration, staff, the city council, city-owned vehicles, equipment, uniforms, employee training, jails, parks, lawn mowers, playground equipment, lighting, public parking, payments to contractors and local businesses, programming at community centers, or projects for community enjoyment like Movies and Moonbeams. In essence, taxes are dues to be part of a community, like a membership to a gym.

In the end, the city derives about 90% of its revenue from taxes in various forms. Even small changes can mean the difference between effective public resources and a breakdown or degredation of services. We’re not talking Lord of the Flies here, we’re just talking about a gradual erosion of public services that are easy to forget because many of them are so commonplace as to become invisible.

Back to the City Tax Renewals

But wait, this article isn’t about taxes in general, it’s about the damn tax renewals, so let’s get back to that. Now that we have a better understanding of how taxes are assessed and what the city’s portion of your property taxes is, let’s look closer at what we’re being asked to do. The tax renewals are broken down like this:

Proposition 1 – Street Improvements: 1.120 mills

Proposition 2 – City Parks: 0.830 mills

Proposition 3 – City Employee Raise: 1.120 mills

Proposition 4 – Police/Fire Uniform Allowance: 1.120 mills

Proposition 5 – City Employee Pension/Health: 1.690 mills

Proposition 6 – Three Platoon Police System: 1.470 mills

To calculate the dollar costs, it is as easy as moving the decimal point one place to the right assuming a $100,000 property or $10,000 taxable value. So now it looks like this:

Proposition 1 – Street Improvements: $11.20/year

Proposition 2 – City Parks: $8.30/year

Proposition 3 – City Employee Raise: $11.20/year

Proposition 4 – Police/Fire Uniform Allowance: $11.20/year

Proposition 5 – City Employee Pension/Health: $16.90/year

Proposition 6 – Three Platoon Police System: $14.70/year

That’s a grand total of $73.50 per year for all six of these initiatives on a $100,000 property – or $25 less than an Amazon Prime account or $58 less than a year of Netflix. If there are three people in the home (the national average), that’s less than $25 per year per person.

With that, let’s review the purpose of each proposition. Keep in mind the above costs as you read.

Proposition 1 is for streets. Significant headway has been made in recent years in planning and executing a street improvement plan. A few years ago, this was many Shreveporters’ number one complaint about public infrastructure. New overlays and upgrades can be seen in every district and more roads are on the way. Maintenance (like fixing potholes) is crucial not just for safe, comfortable travel, but for protecting the larger investment of a road over time. Without repair, roads with cracks and potholes degrade rapidly and cost more, in the end, to repair if not addressed in the early stages of deterioration. While the funds from the millage are a fraction of the total money spent on street improvements, it helps to alleviate these concerns that we all care about.

Proposition 2 is for city parks. It is intended to provide materials and equipment to facilitate everything from summer camps for kids, bingo for seniors, to playground upkeep, Movies and Moonbeams, or to the support given to festivals like Crawfest, Red River Revel, and Prize Fest (the latter one I’m a part of). Things break down, need repairing, replacing, or need to be purchased for the first time. Basketballs and lawnmowers don’t last forever, and this gear gets a lot of mileage. Plus, there are new community centers opening to better facilitate those in need of programs to keep kids off the streets and engaged in learning and physical activity.

Proposition 3 about the City of Shreveport as a competitive employer. Believe it or not, the people working for the City are not volunteers. The roughly 2,500 people the City employs have mouths to feed and bills to pay. They are paid employees who could go into the private sector if they so choose and some have, indeed, been poached recently. If compensation is uncompetitive, talented people are less likely to apply to or stay with the city. Every employee lost means time and energy spent searching for, interviewing, and training new staff. For employees like police officers and firefighters, this training is lengthy and costly. High turnover rates mean lost productivity and waste, less turnover means less waste and, with a healthy and competitive benefits package, more qualified applicants will apply, meaning city services are likely to be better staffed, further reducing costs through the sheer fact of having better employees. Additionally, the City of Shreveport has a minimum starting wage of $10/hr for all employees.

Proposition 4 is for additional funding for public safety equipment like fire trucks and police cars. The people that protect us need equipment that is functional and ready to serve whenever they are. There are some newer police cars on the road as of 2016, but the city is purchasing them in increments to make sure that use-related malfunctions don’t hit the fleet all at once. Prop 4 is also a lot like Prop 3 in the sense that it is also part of a competitive compensation package. Every officer and firefighter is responsible for purchasing and maintaining their uniform. When you work every day in these professions, having multiple uniforms is essential. Prop 4 gives an allowance to public safety officials so that they don’t have to spend their take-home pay on uniforms. Essentially, this funds a take-home pay raise for those that protect us. And, as with Prop 3, higher take-home pay is part of being more competitive and allows for higher attraction rates and lower turnover.

Proposition 5 is also about employee compensation – specifically pension and health. The state requires police and fire pensions. It’s non-negotiable. Part of this fund will help offset those costs. Additionally, as a part of the city’s employer competitiveness, this proposition helps fund city employee healthcare, life insurance, and pensions.

Proposition 6 is set to help maintain Shreveport Police’s Three Platoon System. This system allows there to be police protection 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. SPD maintains three platoons (hence the name) working 8 hour shifts. More time on patrol means increased need of staff, additional miles on the cars, administrative support, etc. Although the program and it’s public funding is staying exactly the same, it is the first year this proposition appears on the ballot before voters because the state now requires it to be a ballot initiative.

The Trouble with Comparing Cities

While there are similarities in city structure that result in consistent results like the illustrations above, it’s really hard to compare cities using property taxes as a metric because each municipality uses different mechanisms to fund their budget (sales tax, property tax, permits and fees, state taxes, grants, etc) and is highly dependent on a number of factors. Take Memphis for example. As we discussed above, the City of Shreveport assesses property is assessed at $3.58 per $100 of assessed taxable value. Remember, a $100,000 home pays $358 per year in property taxes. Memphis taxes at a rate of $3.27 per $100 oftaxable value. However, trash collection is not included in the property or sales taxes collected by the City of Memphis and is its own separate fee of $22.80/mo on the water bill.

Adding those two together means that this theoretical Memphis property owner pays $327 plus $273.60 for trash collection, or $600.60 total. That means, on this metric alone, Memphis property taxes appear to be lower than Shreveport, but when calculating the real value of what we pay here in Shreveport, the paid dollars are higher in Memphis as a result of costs that are charged elsewhere.

But even that’s not fair, because the sales tax in Memphis is 9.25% while ours is 10% and rolling the trash collection fee in to compare to property taxes discounts the other tax inputs that might otherwise contribute to providing the services they do. This is why it is incredibly hard to make a comparison like this, and therein lies the danger in making comparisons about property taxes. It’s incredibly hard to compare apples to apples.

Why Shreveport Has Higher Taxes

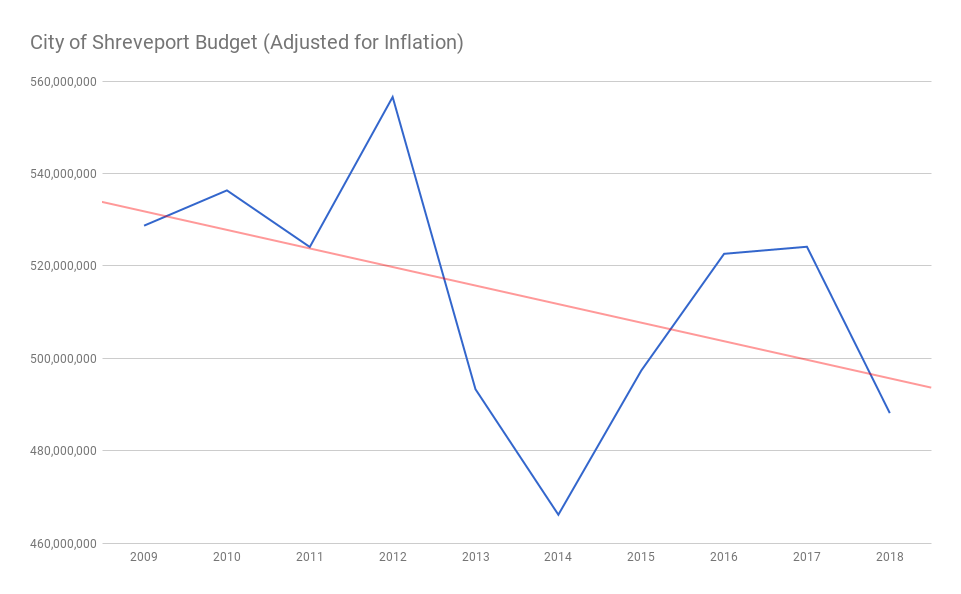

First things first, Shreveport’s taxes are 35% lower today than they were in 2001. Reductions in property taxes have occurred every year since 2014, dropping 15% over those four years. In large part, this reduction is a result of the city proactively paying off debt which, in turn, can be taken off of our tax roles. When adjusting for inflation, the city budget is $30 million less today than it was in 2009.

I’m going to skip the argument where we talk about what the city could cut in order to squeeze $11 million out of the budget. The whole community got into an uproar a couple of years ago and demanded that the City continue to provide trash services directly instead of privatizing it or charging a separate fee. Similarly, people got defensive about privatizing the water system (an opposition I agreed with). So the majority can’t both be simultaneously for lower taxes AND for keeping services with the city. With that inconsistency aside, we can move onto exploring why we have higher taxes than most of the state.

The first thing is to remember that Shreveport citizens don’t just pay taxes to the city. As was outlined earlier in the piece, the city is just one of several entities that can tax your property. 78% of your property taxes go to things other than the city and its services.

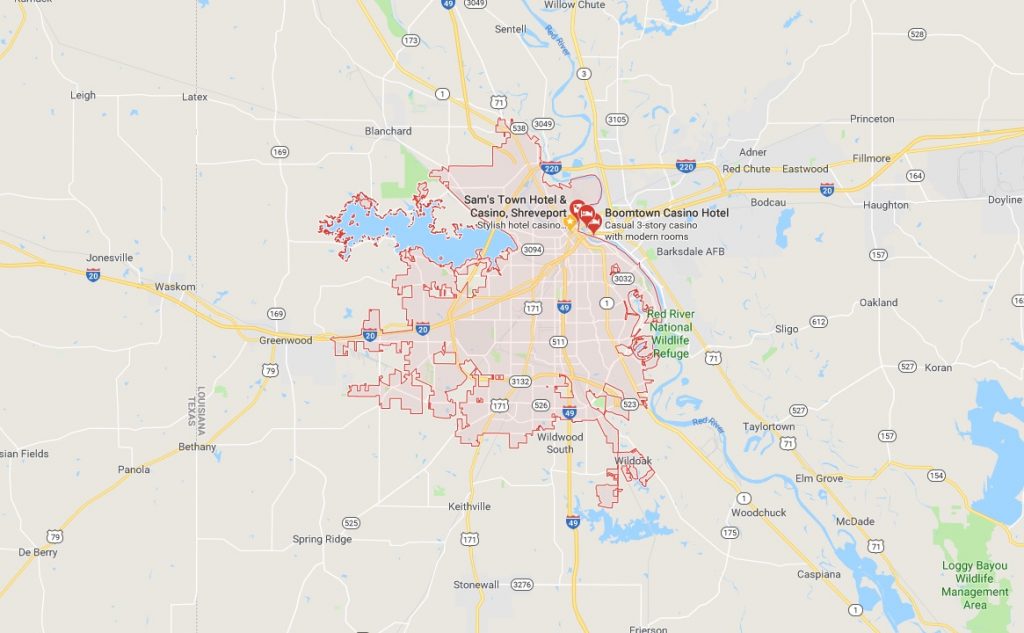

Looking beyond this particular tax renewal, the reality is that Shreveport’s population is in a backslide and has been since 2001 and accelerating through 2010. We discussed this in depth in another article. The 2020 census is looming and we’re probably going to get smacked really hard with another precipitous drop. We’ve talked about city development issues and sprawl in Heliopolis time and again, and all of this comes down to the simple fact that the city is geographically too large for the number of people funding our public services.

Fewer people means fewer taxpayers which means the rest of us share a responsibility to keep the city services we want and need afloat. Yes, if we had more people there would be an increase in city services to go along with it, but we are already paying to service empty houses and vacant lots with all the police, fire, sewage, streets, etc, so the real world effect would be a net decrease in taxes with more people living in the same geographic area. If people really want to pay less in taxes, there are more practical approaches that I’ll touch on now.

Practical Approaches to Lower Taxes

1) Grow the City Population We could work to aggressively attract more people to the area by making it an easier place to start a business – particularly 21st-century businesses that have high paying salaries and low footprints. But in order to see a significant reduction in city taxes, the city would need to add tens of thousands of people within the current city footprint, using mostly the same amount of infrastructure. That’s a pretty steep increase considering our current predicament, but we can absolutely fit that many people (and more) in the existing city limits. Any progress we might have is currently being hindered by a lack of the following points.

2) Better Wages Businesses could voluntarily pay our citizens more as an investment in future business and community betterment. If businesses paid employees a living wage, we wouldn’t need to consider a minimum wage. Real world studies have shown time and again that increased wages leads to reduced crime, lower public health costs, and thus better communities. In real terms, more take-home pay for everyday Shreveporters means increased discretionary spending which spurs economic activity and a more evenly spread tax responsibility. But, for many businesses, it’s hard to justify an increase in labor costs when there’s no one to pay higher prices. It’s a chicken and egg issue – except I know the answer to this riddle. It’s next on my list.

3) Education Man, we have been needing to have this conversation for a long, long time. In the opinion of this writer, our education system, while getting better under the direction of superintendent Dr. Theodis Goree, is still the lacking sufficient change needed to best suit the needs of 21st-century students, businesses, or the community. What skills are kids graduating with? What career pipelines are we creating and how does that feed into our desires as a community to attract and foster new business? There are early steps occurring, but every year that passes without significant redirection is another graduating class that gets less than it deserves.

We can and should focus on educational effectiveness and create a better school system that’s centered on career objectives and soft skills instead of rote memorization and college preparation. The best part – such a change shouldn’t cost us anything but giving credence to the criticism and making an effort to change it. There are models working elsewhere in America that are perfect for exactly the kind of scenario we’re in and can create a workforce pipeline that is attractive to existing and future employers.

4) Limit Liabilities We could (and I will argue we should) reduce the size of the city geographically using a formula that compares property value and cost to the city to service those properties. We can keep the most productive properties, and de-annex the rest back to the parish. Those de-annexed properties are free of city taxes and the City can then focus its efforts on using the resources it has most efficiently. The reason for de-annexation is simple – the outer edges of the city are the least dense. This means, despite having larger and more valuable homes, each property costs more to service than those in the city core.

Every mile of road, every inch of pipe, every foot of sidewalk, every minute on patrol is money spent. Infrastructure is a liability, destined for disrepair, not an asset as it is listed in the city ledger. If our city were denser and less spread out, as the center of the city was designed to be over 180 years ago, we could improve the cost of service ratio to make better use of the funds the city has. It might sound counterintuitive to let taxpayers leave the city but, done right, the math works. If it turns out that “high value” properties in the southern part of town cost more to service with roads, pipes in the ground, and police/fire coverage than they are paying in taxes, then why are we subsidizing those properties at the expense of quality service in Highland, Lakeside, or Broadmoor? Is that the case? No one knows because no one has bothered to do the math.

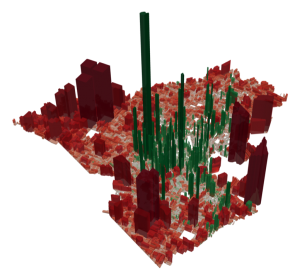

There is, however, compelling evidence that it would be the case if we actually ran the numbers. Lafayette, along with dozens of other cities, has done the math. We can see on the image below where Lafayette’s property value to city service ratio is best (hint: it’s the city core, illustrated in green). The areas in giant red blocks, representing negative revenue to the city, are their equivalent of Youree Drive and subdivisions and other unproductive tracts. The short story is the red zones cost more to service than they bring in revenue. The green areas which are denser urban neighborhoods are, in effect, subsidizing the lifestyle of sprawl. This is why I preach the city core/downtown bible. It’s about fiscal responsibility as much as anything else.

A property value study, like the one done by Urban3 in Lafayette, isn’t that expensive as far as studies go. This $30,000 investment could help us determine, lot by lot, where to invest our public resources. But the reality is we already know what to do, generally speaking. We should have this study done to further illustrate the point and to get the granular information necessary for an argument about de-annexation but just look at that map. It’s clear where the value is, and its why savvy investors are grabbing land in the core. I’ll also mention here that denser living means less property and smaller homes, which means your assessed property value is less, meaning that, if you live near the core, you’re almost certainly going to pay less in taxes, even today. At the same time, denser properties at lower assessed value provide far more tax revenue per acre.

Everyone Should be Able to Vote (and They Can)

There is one more assertion being made by some that I want to talk about. That is the idea that only property owners should be able to vote on property taxes. On its face, this is a simple idea: Only allow those who pay the tax to vote on its increase, decrease, or continuance (the last one is what we’re voting on this month). However, it’s just not that simple.

First and foremost, anyone that pays rent pays property taxes indirectly. They pay the rent to the landlord and the landlord pays for the upkeep of the house, the mortgage, if any, and yep, property taxes. Not only do renters pay property taxes and are subject to increases based on the costs related to a rental property over time, renters use the very services that are funded, at least in part, by property taxes. That all goes without saying that property taxes enable the business of renting in the first place. Without the roads, the renters wouldn’t be able to easily get to work to earn a living and pay rent. Without schools and public safety, people won’t pay a premium on rent. Without parks and other quality of life services, homes are less valuable to potential renters.

Another thing that really irks about this argument is that it is sometimes paired with the idea that if the tax renewals go through then landlords will be forced to raise rent. This sentiment is completely and utterly ridiculous. I would love to find the name of a single landlord who lowered rent after the expiration of taxes as the end of 2017 – who shared the savings landlords earned with their tenants. If a landlord didn’t lower taxes after the expiration and is threatening an increase now, they are manipulating tenants using financial pressure to influence voters who are at their mercy.

Conclusion

In the end, if the propositions for renewal fail, you will certainly pay a little less in property taxes, but at what cost? Are we ready to be less competitive when compensating police officers and firefighters? Are we willing to slow progress on road repairs and transportation infrastructure which increases home values? Are we willing to cut back on parks and the services they provide to those who are most at risk? Are we ok with potentially limiting police patrols?

Maybe, if these six propositions fail, some of these services won’t go away. Maybe it will be something else – like trash collection – or maybe it’s a service you really like such as Movies and Moonbeams or the support provided to community events. Or maybe roads get replaced, but not at the rate needed to keep up with normal wear-and-tear. Or, perhaps, the belt will get tighter and the city will wither slowly and everyone will complain about how nothing gets better around here.

To me, there are better and more effective ways to lower taxes that simultaneously build up the community of commerce and quality of life. And no, none of those things are going to happen by themselves. We will have to actively work to make those changes and they should be important topics we discuss come election season this fall.

To me, there are better and more effective ways to lower taxes that simultaneously build up the community of commerce and quality of life. And no, none of those things are going to happen by themselves. We will have to actively work to make those changes and they should be important topics we discuss come election season this fall.

Until then, I encourage you to vote YES on all six propositions and urge you to drag your friends and family to the polls (find your polling location here) where I would encourage them to do the same. Then we, as a community, should turn around and do the hard work and make the hard choices to bring about real change in the way our city is built to truly be more effective at reducing costs as a result of hard work and critical thinking. I will be voting YES on all six propositions. I love Shreveport too much to do anything less.