On Monday, March 13th, Joe Minicozzi of Urban3, gave an hour-long presentation of his company’s assessment of Shreveport’s land value, our struggling roads and water infrastructure, and the ability of our local tax system to pay for repairs. The whole thing can be a bit nerdy, but Shreveport’s future will depend on our ability to understand and willingness to act on this new information.

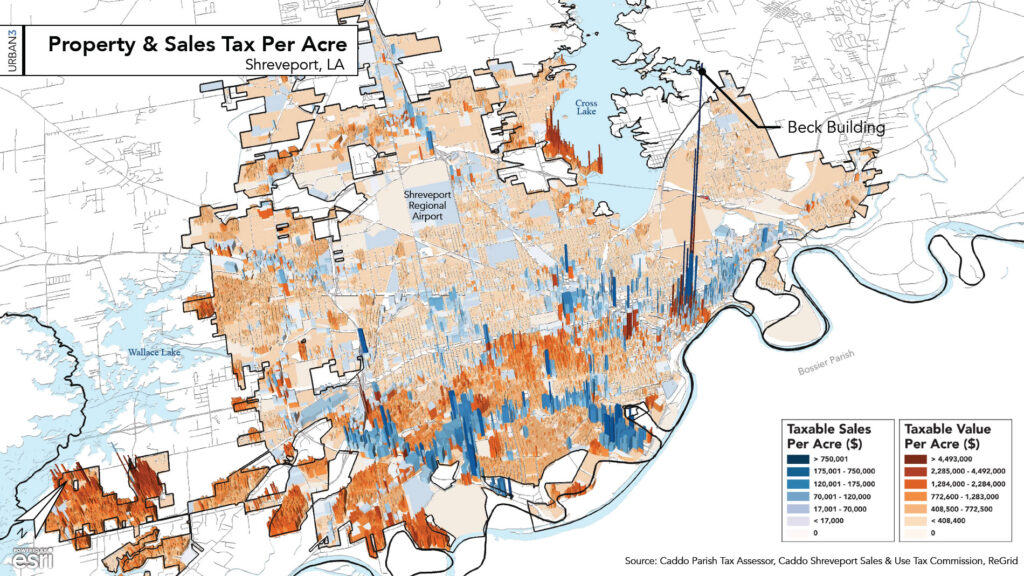

Urban3’s study was commissioned by the City of Shreveport and paid for by CARES Act funds from the federal government distributed under President Trump with matching funds from the Downtown Shreveport Development Corporation (DSDC). The team at Urban3 analyzed every single parcel of land in Shreveport and collected property tax numbers (provided by the Caddo Assessor’s Office) as well as sales tax information for every business in the city. With this data, Urban3 could determine, for the first time ever, which building types and areas of town held the most value to our city’s revenue line.

After running the numbers, it was determined that dense urban development, especially multi-story, multi-use buildings, results in the highest property values. Sales tax, of course happens where there are the most sales — be it retail or business to business. The striking value of dense, multi-use buildings and the power of a centralized business district is visible in the huge blue spike found in downtown Shreveport. This set of spikes is massive, even with most of downtown sitting unused.

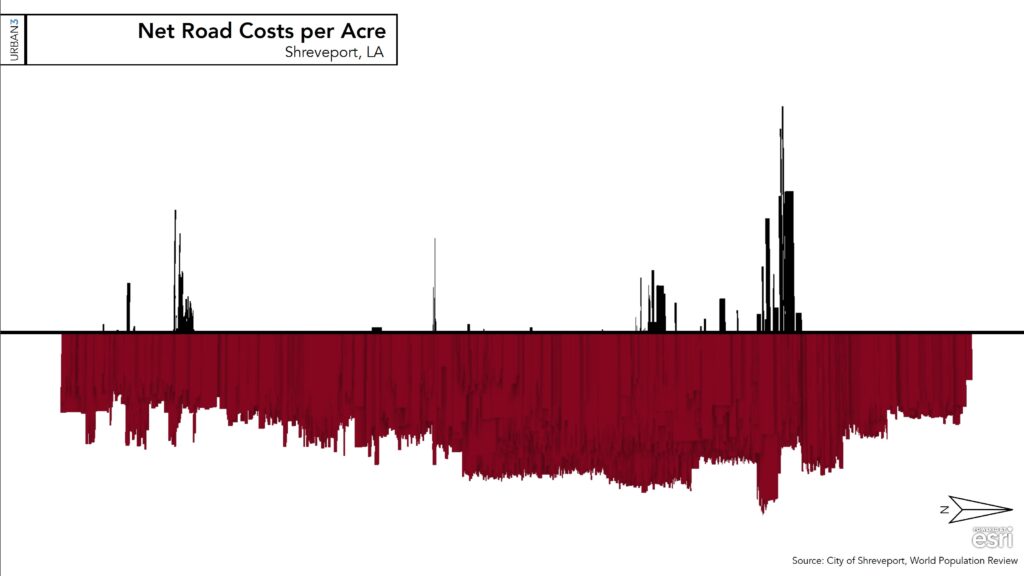

As you can see, just about every part of the city is raised off the map, showing the combined property and sales tax value they provide to the city. However, revenue is just one-half of the story. The second half is expenses, or how much money it takes to repair and replace the roads, sidewalks, water, sewer, and other public services we need to make that land usable. Urban3 compared the taxes collected against the cost necessary to service each acre of land. With both tax revenue and expenditures taken into account, the map looks like this:

This graph reveals that almost all of Shreveport is upside down on public infrastructure (depicted in red) compared to areas where there is more revenue than expenses (depicted in black). What this shows is that we put more infrastructure into our city than we are getting out in return, indicating an unsustainable revenue model for Shreveport. This is the answer we’ve been looking for. This is why we can’t afford our infrastructure. We don’t make enough back in taxes to pay for what we’ve built.

The natural follow-up question is: “How did this happen?” Moreover, “What can we do to fix it?”. The answers are multi-pronged, so let’s start unpacking them.

1. We have too much land and infrastructure responsibility for the number of taxpayers in Shreveport. First, knowing that Shreveport is not alone in this challenge is important. Cities across the United States grew after WWII, largely through increasing their footprint with homes that favored large, expansive private lawns over parks and public spaces. These neighborhoods were also often built without businesses, except the occasional grocery store or gas station nearby, which reduces the amount of sales tax collected in a given area. The farther out we go, the less commerce and more residential property there is.

Part of the problem with sprawl (and I can’t stress enough that it’s only part of the problem) is that Shreveport’s tax system was designed for dense, urban development with low per-property infrastructure requirements and a focus on collecting sales taxes, not so much property taxes. Without changing our development practices to focus on dense, mixed-use residential and commercial redevelopment of the city core, Shreveport’s tax system will always fall short.

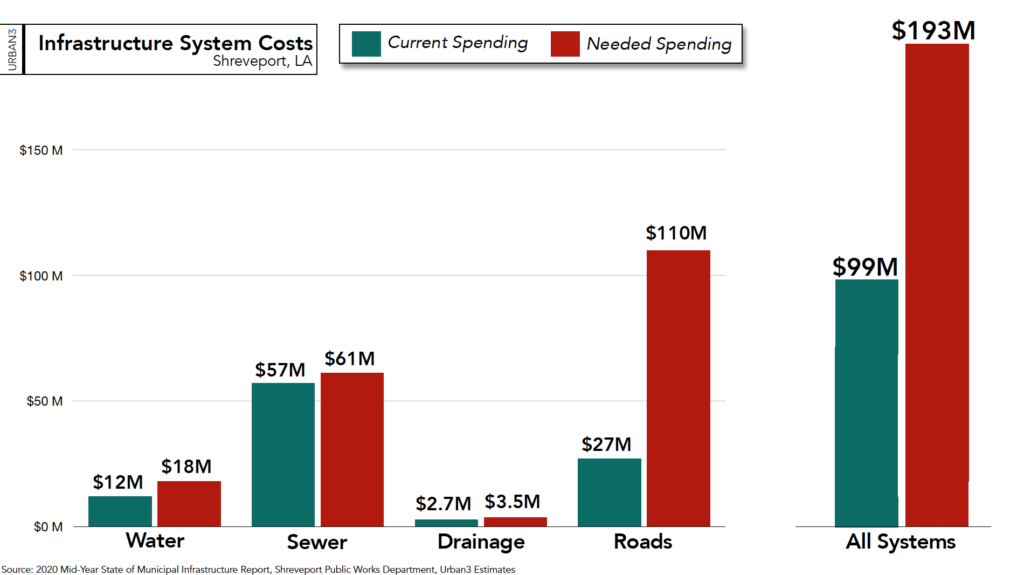

This shortfall is made abundantly clear in the infrastructure system cost graph below, which identifies that we are short nearly $100 million in infrastructure spending per year, almost entirely because of roads — the magical, freedom-providing infrastructure that was championed by post-war Amerca propaganda films (click to watch) which ultimately led to our car-dependent communities.

2. Our tax system is not right for the city we have (or the one we want). While mostly dependent on sales tax, Shreveport’s tax system also fails us on the property tax side of the equation. Because we base property taxes on what’s built on the land rather than the market value of the land itself, our current system favors speculation and vacancy.

This means that it is cheaper for someone to hold onto an empty plot of land for speculation on its future sale price or pave a surface parking lot (which I contend is just speculation with a little mailbox money) instead of constructing a productive building. This system also discourages property owners with existing buildings from making improvements, or worse, rewards them for letting buildings decay as has happened time and again, creating blight and safety hazards.

If we taxed a property based on what the market determined the value of that land was instead of the value of the buildings upon it, it would be more expensive to speculate or sit on land but cheaper to build on. That kind of tax environment, also known as a land value tax or LVT, would spur the redevelopment of “legacy” neighborhoods and reward those who add value to our community.

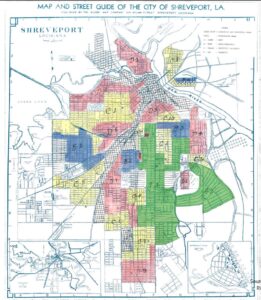

3. We redlined and divested from core, legacy communities. In the 1930s, the United States added requirements to determine which neighborhoods qualify for government-backed mortgages. They used color-coded maps with four grade levels: “A” for the most desirable properties (colored in green), “B” and” C” for middle to low-grade properties (blue and yellow, respectively), and “D”-graded properties (in red) for the least desirable lands. A grade of “D” was almost always given to communities primarily consisting of black and immigrant residents. This process became known as “redlining” (listen to a brief history of redlining here).

The notes accompanying Shreveport’s redline map specifically included percentages of “negro” to “white” residents as factors in how neighborhoods were rated. For example, one note for Section D-3, which is the northern part of the Highland neighborhood just south of where I-20 sits today, read, “White residents of this section, moving away as fast as they can, [are] disposing of their properties due to detrimental influences of negro population…” while Section D-3 is noted to “contain a small area of white population, older citizens of the city of the better class who still maintain their homes.”

Of course, it is no secret that Black residents of Shreveport suffered heavily under the social and economic impacts of Jim Crow, hindering their ability to make wealth gains that would provide for property improvements, business investments, and political representation that would have garnered a better grade.

No bones about it, these redlining notes, and others like them, cast Shreveport’s white flight in sharp relief and demonstrate a key reason why core communities were abandoned: outright racism and a splash of classism for all low-wage earners. Instead of staying in core neighborhoods and working to improve the education system, parks, institutions, and representation that could unify the city, middle-class and affluent white people fled and took their money and business with them. This ultimately led to a hollowing out of the city’s core and accelerated the detrimental sprawl of the city.

4. We make it difficult for individuals and developers to rebuild the core. Our zoning codes and permitting processes could be more conducive to redevelopment. For example, we eschew building types like multi-family homes, small/tiny homes, and mixed-use through written rules or zoning approval preferences. We also have minimum parking requirements, forcing developers to provide a certain amount of parking that often goes unused. Plus, parking lots are wildly unproductive from a tax standpoint because our current system is based on what sits atop the land, not the market value of the land itself. A land value tax would make building parking lots even less desirable for developers, so we should eliminate or significantly reduce that requirement.

We also have a history of over-zoning our city. Rules that protect residents and property values, such as how close industrial sites or loud businesses can be to residential areas, are a valuable concept. However, there is a limit to its usefulness, past which zoning can become detrimental to redevelopment. To defeat this, we must reconsider our zoning rules (again) and direct our planning commission to learn how to get to “yes” without being “yes men” through reasonable and expedient compromise, especially on codes that conflict with the ability of historic buildings to comply without expensive retrofits. The goal should be to get properties to occupancy and revenue quickly and safely, allowing for exemptions or gradual compliance where necessary.

In this writer’s opinion, Urban3’s analysis and the problems it underscores are a biting critique of Shreveport’s development and tax strategies. While they were generally accepted across the country when they were implemented, we know better now. Their faults were masked by explosive post-war growth as well as the delayed timeline of infrastructure replacement, which came due just as Shreveport’s population growth faltered in the 1980s. We have since seen the effects of these choices. The community even wrote a whole Shreveport-Caddo Master Plan aimed at addressing many of these challenges, but elected officials and department employees have largely ignored it.

A kind interpretation would be that they don’t understand that their jobs would be made easier by following the Master Plan and the recommendations made by Urban3, ReForm Shreveport, and others. There is now overwhelming documented evidence that our approach of “chasing the tax base” by continuing to annex land and abandoning the city core continues to be a losing proposition for everyone except those who profit from such sprawling developments. No amount of bonds or new neighborhoods the suburban edge will bail us out from that approach, and doing nothing to change these practices will sink us further into debt and drive more people away from our city.

Based on the analysis results, ReForm Shreveport has made a list of action items that aim to address the above issues and others that Joe outlined in his presentation. The action items aim to increase economic opportunity, rectify policy decisions based on racism and anti-immigrant sentiment, and help pay for the things we need without raising taxes.

From the ReForm Shreveport website:

The sooner that these changes are made, the sooner the city can begin to recover and the sooner it can address its ailing infrastructure and quality of life. Shreveport residents, communities, businesses, and nonprofits should press the City of Shreveport to act quickly on the following items:

- Make targeted investments in the construction of dense urban developments — both residential and business-oriented — in areas that have suffered past policy choices that will return more than our investment. This is primarily in previously redlined communities in the city core and west of I-49.

- Remove zoning barriers to multi-family homes, small homes, and other dense multi-use buildings to in-fill our legacy communities and use the existing infrastructure to maximize returns to the city’s tax revenue.

- Work with local historians, architects, and students to create free, pre-approved home plans for legacy communities to be built with minimal time and cost. These designs should be sensitive to legacy neighborhood historical styles and sensibilities.

- Make communities more walkable and conducive to multiple types of transportation (including bicycles and public transit) to reduce dependence on expensive roads and parking lots, which are low-return land uses.

- Remove parking minimums which force developers to spend money and use land unproductively.

- Open a discussion about de-annexing outlier areas of town that consume more city tax resources than they provide.

- Replace the current property tax system with a Land Value Tax (LVT) system that incentivizes redevelopment and disincentivizes speculative land purchasing, leading to underutilized and vacant properties that plague downtown Shreveport and some legacy neighborhoods. We should also consider reducing our reliance on sales tax, as sales tax tends to suffer during economic downturns, which are largely out of our control.

- Because we know what infrastructure we have and what needs replacing, create a policy that saves tax revenue for future repairs to be paid for in cash, saving taxpayers from paying interest on bonds for regular maintenance. Reserve bonds only when taking on debt and interest is necessary and unavoidable.

- Make all changes with a focus on addressing past wrongs and ensuring that displacement does not take the place of long-time residents of core communities. Be intentionally inclusive of current and potential minority landowners, developers, and residents.

Watch the complete video presentation below and download the slideshow here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n2AFtq59OAw