Disclaimer: The author is also working with Citizen She to educate voters about the Unanimous Jury law.

Louisiana Republican and Democratic Parties have both endorsed a significant Constitutional Amendment tucked at the end of the ballot in the upcoming election.

Louisiana is one of only two states where someone can be convicted of a crime without the agreement of a unanimous jury. We are the only state where someone can be sentenced to prison for life, even if 2 jurors don’t think the person is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

In addition to garnering endorsements from major political parties and singer John Legend, groups across the political spectrum, from conservative Louisiana Family Forum and Americans for Prosperity to progressive ACLU and Voice of the Experienced (VOTE), support a ballot measure to change the law. The New Orleans Times-Picayune, The Advocate, and New York Times Editorial Boards have backed it, too.

Heliopolis talked with Will Snowden, a member of the Unanimous Jury Coalition, a collective of organizations focused on criminal justice reform that is educating the citizens across the state about the history of non-unanimous juries. Snowden is also the Director of the Vera Institute of Justice-New Orleans Office.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Heliopolis: Would you tell me about this current law in Louisiana? Why is it unusual?

Will Snowden: The founding of our country was really premised on ideas about individual liberties: when the government tries to take away your liberty, that should be a big deal. Therefore, when prosecutions are going forward, we want a conviction to be sanctioned by all 12 members of the jury of our peers. However, Louisiana laws say that the voices of 2 people on the jury don’t count.

H: If criminal convictions in 48 other states require unanimous juries, why is Louisiana different?

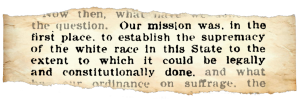

WS: The non-unanimous jury law was codified at the Louisiana Constitutional Convention in 1898. When the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, with the exception of criminal punishment, there were 134 Confederate Senators as this Constitutional Convention trying to figure out what they were going to do with 400,000 newly registered African American voters. One concern was that, if you are registered to vote, you can also be on a jury.

So, in 1898, juries changed so that a guilty verdict from only 9 of 12 jurors would carry for a conviction. In 1974, [split-jury verdicts] were changed to 10-to-2, which is what we have today.

The Convention’s transcripts are clear that law was founded upon diminishing the power and influence that African Americans could have on a jury. This is a vestige of Jim Crow. It’s rooted in racism and doesn’t belong in our criminal justice system.

H: Is there evidence of non-unanimous juries making a significant impact on court proceedings?

WS: In the past 6 years, about 40% of criminal convictions were decided by a non-unanimous verdict. We’ve also noticed that African American defendants are disproportionately convicted in non-unanimous verdicts when compared to white defendants.

Since 1989, we’ve had 12 individuals, so far, that have been exonerated who were originally convicted via a non-unanimous verdict. That means that when these people went to trial for the first time, there was either 1 person or 2 people that voted not guilty, but since we don’t require unanimous verdicts, those individuals were unable to prevent that innocent person from going to prison.

H: Why is that problematic for our courts?

WS: Generally, it’s easier to convict people that go to trial when the law doesn’t require a jury’s full agreement. In fact, prosecutors have been on the record saying that they will overcharge a particular defendant to get to a 12 person jury because they know they have a higher chance of winning with a non-unanimous verdict.

That’s really concerning because it’s not consistent with the evidence [of a case] but with a tool that makes it easier to convict people. This is not in the interest of justice. It’s not in the interest of the victim. That’s not in the interest of the person going to trial. It’s only in the interest of the prosecutor trying to get a conviction.

When we have a criminal justice system that does not abide by best practices, we should be cautious. If we have a system that produces inaccurate results, we aren’t really providing closure. Having unanimity on a jury takes our criminal justice system into the 21st century because it requires more accuracy. This is the kind of criminal justice system we should all want in Louisiana.

H: What do you think a “yes” vote will do for the future of our criminal justice system?

WS: It is important to vote on this issue because non-unanimous juries have plagued our criminal justice system since the 19th century. We’ve had the entire 20th century with non-unanimous juries. We’ve had the beginning of the 21st century with non-unanimous juries.

When people talk about Louisiana being the prison capital of the world, it’s also important to know that we’re the exoneration capital of the world. What that means is that our juries are getting it wrong more than anywhere else, so we have to ask, “Why is that the case?” It’s because we have non-unanimous juries that make our criminal justice system operate in a manner that is not aligned with our traditional notions of fairness and justice. It’s time for us to advance our demands for the criminal justice system to work for all the people of the state.

For more information about this topic, readers can visit https://www.unanimousjury.org/.