Disclaimer: Elizabeth, the author of this piece, is currently contracted with The Community Foundation of North Louisiana to explore the feasibility of a social entrepreneurship accelerator to benefit Shreveport-Bossier. Additionally, Chris Lyon, the editor-in-chief of Heliopolis is employed by the Louisiana Startup Prize which is mentioned in this article.

Editor’s Note: As we begin to look forward to the election in 2018, Heliopolis is beginning a series of articles on making Shreveport a more progressive and prosperous place to live. Social enterprise is desperately needed in Shreveport in order to diversify our economy and creating stable economic foundation. If you are interested in learning more about efforts to support social entrepreneurship, we suggest reaching out to the author Elizabeth Beauvais at ecbeauvais (at) gmail (dot) com or by contacting any of the local organizations mentioned in this article.

Innovating entrepreneurial solutions for local social challenges

Why do some small cities become innovation and entrepreneurial hubs while others stagnate?

Why are the scourges of poverty and income equality more thorny and intractable in some cities than others, despite public funding and a bevy of nonprofit programs? And if we had a spectrum, with “thriving” on one end and “circling the drain” on the other – where would Shreveport fit?

While there are no easy answers to these questions, a new industry called social entrepreneurship rapidly growing in large and mid-sized cities alike offers promising — and practical –entrepreneurial approaches for non-profit and for-profit enterprises engaged in solving challenging social problems.

By definition, social entrepreneurship is the process by which entrepreneurs build ventures within the existing marketplace to advance solutions to social problems, such as poverty, illness, illiteracy, equity, environmental degradation, human rights abuses, and corruption in order to make life better, both for those that have and have not.

In short, social entrepreneurs build and scale sustainable businesses that have a direct social or environmental purpose.

Social entrepreneurship builds on the blurring boundaries of our increasingly globalized, diverse digital world by challenging the historically compartmentalized thinking around public, private and non-profit silos with a systems-based, cross-sector approach to problem solving. As a result, social entrepreneurship is driving innovation.

Where social entrepreneurs provide the greatest value, however, is in their recognition that a city or community cannot be economically healthy while ignoring the overall health of its residents. As 2013 Nobel Prize winner in economics, Robert Shiller, has pointed out, there is an established relationship between income inequality and economic growth, with more unequal societies showing less robust growth and stagnated economic development over time. Consider the vast gulf of income inequality in our area, felt both in absolute terms (33% of the parish’s children live below the poverty rate), as well as by gender and race (women in Louisiana make less on the male dollar than any other state, and 1 in 3 African Americans in Shreveport live under the poverty line as opposed to 1 in 10 white residents).

Social entrepreneurship does not replace the role of local, state or federal governments, nor that of non-profits who need to rely exclusively on philanthropy to do their mission work – but it does offer a compelling third road up the mountain. It is a road with the potential to shift philanthropy into catalytic funding and inject much needed innovation and financial sustainability into the social sector. And like any new industry, a supportive ecosystem is needed incubate ideas, provide mentorship, partnership and networks, and accelerate growth and success by connecting social entrepreneurs with resources.

Social entrepreneurship incubators and accelerators have been mushrooming in mid-sized cities not too different from ours in recent years.

- In New Orleans, Propeller acts as both an accelerator and incubator to support and grow social innovation and entrepreneurs who are working to solve the key challenges that hold their city back: food access, water management, health and educational equity.

- A major entrepreneurship accelerator in Memphis, Start Co., built a social entrepreneurship program called Sky High, strategically aimed at building game-changing innovations that address a single, critical local problem: education and the digital divide.

- Flywheel in Cincinnati helps social entrepreneurs build and scale businesses that have both a financial return and social impact. Their consulting, mentoring and accelerator programs promote social enterprises by connecting them to customers, talent and capital.

- In Charlotte, Queen City Forward provides a hub for entrepreneurs who have business ideas that address social needs and work to balance a triple bottom line of people, planet and profit. The group encourages, enables and scales these social enterprises to create a robust cluster of innovation in the Charlotte region.

These efforts are producing new marketable ideas to local social and environmental issues in ways both exciting and innovative. Consider:

La Soupe (Cincinnati, OH) was formed to bridge the gap between food waste and the food insecure. In 2016, they saved 125,000 pounds of food from the landfill and donated over 95,000 servings of soup to hungry Cincinnatians, saving both taxpayer money and providing a service for those in need.

La Soupe (Cincinnati, OH) was formed to bridge the gap between food waste and the food insecure. In 2016, they saved 125,000 pounds of food from the landfill and donated over 95,000 servings of soup to hungry Cincinnatians, saving both taxpayer money and providing a service for those in need.

Ready Responders (New Orleans, LA) is a community paramedicine group improving access and quality to healthcare while reducing response times by integrating part-time Emergency Medical Technicians into municipal 911 EMS systems, adding capacity to the existing system.

University Medical Center Urban Farm (New Orleans, LA) is an urban farm on the University Medical Center campus in Mid-City, focused on redefining food culture in a healthcare setting to reduce the burden of obesity-related chronic diseases.

Looptworks (Portland, OR) uses the excess trimmings discarded by apparel and textile factories to make bags, apparel and accessories. Looptworks saves companies landfill tipping fees, reduces waste and water, employs fair labor practices. The company teamed up with Portland Habilitation Center to employ adults with disabilities at a living wage.

Schoolzilla (Oakland, CA) is a software that organizes instructional and managerial data to help teachers and school leaders save time and operate more efficiently.

Could social entrepreneurship work here?

There is certainly a need in Shreveport. Our region faces major challenges that undermine economic growth citywide and the well-being of so many who live here – from very high poverty rate and yawning gap in income disparity, to discouragingly low health outcomes, some of them (such as low-birth weight babies) the worst in the nation.

We also have significant strengths, such as low cost of living and livability, and strong multi-generational relationships that help serve as sources for “social capital” — which is reputation capital found in places where everyone knows “mama and them,” useful for leveraging resources and investments, particularly among those with limited monetary capital and collateral. We have a burgeoning entrepreneurial and creative culture, thanks to the efforts of the Entrepreneurial Accelerator Program, the Louisiana Startup Prize and Cohab. And our philanthropic and non-profit sector are comprised of dedicated, purpose-driven individuals who are willing to take a long view on the importance of investing in and working towards the overall health our community.

Social entrepreneurship itself also carries challenges, some surmountable and others a little thorny, which would need to be woven into the design of any effort. Because these organizations prioritize mission equal to or above profit, and their core stakeholders are often the most vulnerable and impoverished, earnings tend to be marginal at best. Impact investors in this space have to think beyond quarterly returns and news and election cycles, and more in terms of institutional or societal change. As a result, social entrepreneurs need to find what is called “patient capital” from investors willing to factor social or environmental impact timeline and returns alongside the financial. Accessing growth capital can also be a challenge. Traditional start-ups raise money to grow through well-established capital markets by issuing stock or taking on debt. While there are some new creative financing models, and new social impact investors, these innovations are largely embryonic. According to many social innovation experts, government funders, which have the deeper pockets to support growth, would rather pay for services that fund the building of institutions.

Survey research across this industry in the past decade reveals that where social entrepreneurs were trained and able to do what successful business people routinely do: create multi-year growth plans, raise up front capital to execute those plans, and evaluate their performance against pre-established goals – they succeeded. The challenge is that practitioners must adapt that business planning format to organizations that seek to cause social change rather than earn profits – a simple overlay won’t work. Some private sector principles simply don’t translate. Michael Edwards, in Just Another Emperor – the Myths and Realities of Philanthrocapitalism, states that long term social transformation is neither easy to measure nor always cost effective in profit maximizing terms (consider the civil rights movement). Michael Sandel, in What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, discusses the corrosive tendency of markets, pointing out that inequality (in a society where so much is for sale), lack of means means lack of access. Further, he examines how commercialization can also distort incentives for lenders, citing as an example the private prison system in Louisiana, which benefits from high incarceration rates. Finally, a lack of vision around innovation and creativity can challenge success.

Successful social innovation in Shreveport will mean finding and engaging partners and investors willing to think creatively and open-mindedly about both opportunities and challenges. With the right design, a social enterprise accelerator could have a catalytic effect on our city. Consider, for example, the healthcare industry. While Caddo Parish’s ranking on preventable “diseases of poverty” (type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, malnutrition) is among the worst nationally, we also have a world-class teaching hospital that draws researchers and specialists from around the world. We are home to the Biomedical Research Foundation and four local colleges and universities with degree programs that range from engineering to computer programming to nonprofit management. Where might innovation take root and have both impact and sustainability if the right partnerships and incentives were designed as scaffolding around these factors?

For the past several months I’ve been working with the support of the Community Foundation to design a roadmap for supporting and accelerating social entrepreneurs in our region, including training, coaching, partnering, and locating best-fit financial vehicles. The wheels are turning and gaining traction, but it’s the direct work to support existing social entrepreneurs that’s yielding the most valuable mileage.

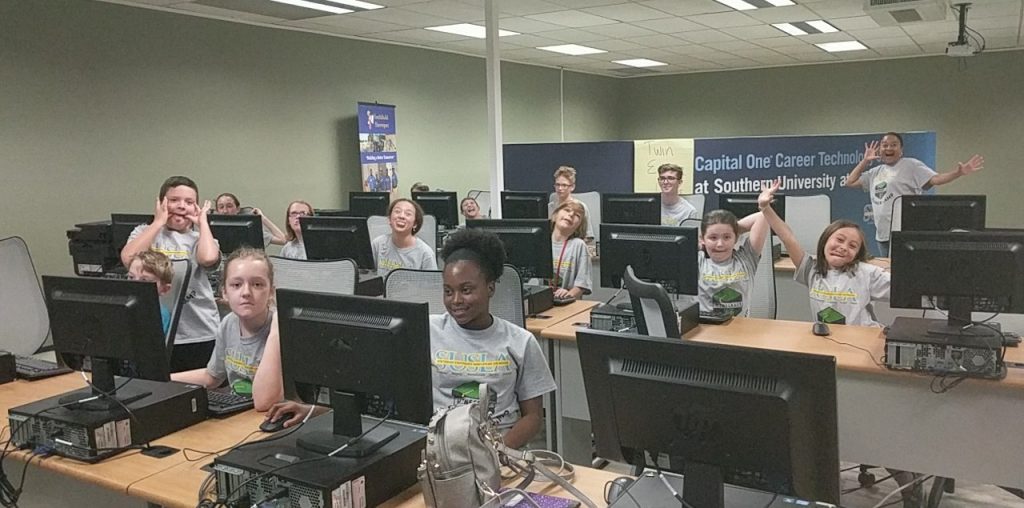

Case in point, I initially approached Keith Hanson, CEO and Founder of Twin Engine Labs, to ask him what he needed as a traditional entrepreneur during his first couple of start-up years. Keith lamented that what he needed in the early years was what he needed now: a steady pipeline of talented local programmers available for hire. As we discussed the concept of social entrepreneurship, Keith, a serial-entrepreneur and visionary, realized that he could build a bridge between the shortage of programmers in the area and the lack of practical IT education for local youths. In a matter of weeks, he established MinecraftU Shreveport, a new organization aimed at creating and nurturing a diverse pool of local, competitive talent in technology by offering computing and programming concepts to kids of all ages in NW Louisiana at no cost.

Hanson, along with other local tech company leaders, sees the value in reversing the pattern of local tech companies forced to hire long distance or overseas programmers through this social entrepreneurship initiative.

“If Northwest Louisiana could create a pool of talent that is globally competitive, the region could see a flood of demand from across the country for our kids’ bright minds,” said Hanson. “Given the lack of options for so many young people in our region, the impact could be huge.”

MinecraftU is partnering with SUSLA, the Caddo Parish School Board, the Shreveport Chamber of Commerce and other local technology businesses to build more accessible and effective IT education through free camps and clubs, all of which will help create more quality jobs and offer many young people a future they might not have had otherwise.

Other local social entrepreneurs are also finding innovative new ways to bake social change into their business model.

Peter Lyons, of the new Lyons’ Pride Coffee, views incorporating a social mission into his coffee roasting and distribution business as a valuable differentiator that allows him offer greater education services, build a stronger network of partners and grow a larger and more loyal customer base. Lyons Pride Coffee will offer individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) a protocol-based SMRT hands-on work training program in the 10-step commercial brewing process. Certifying IDD individuals in a standardized process dramatically increases their employability and quality of life, as well as improves the diversity and inclusion of the overall local workforce.

Omari Ho-Sang’s ASAP Shreveport uses entrepreneurial approaches to respond to the root causes of poverty through marketing campaigns and programs that run as small businesses, such as the ASAP Shreveport summer job training program. ASAP Shreveport is also working to create an app, appropriately named Asapp, which connects volunteers, students and community leaders to each other around specific community service causes and efforts. The app ties in social media platforms to increase impact and connectivity and, when fully launched, will help stimulate the local economy by linking organizers and volunteers to supportive local businesses.

Because success looks different for social entrepreneurs – less about a rocketing IPO and more about achieving financial sustainability and measurable social impact – what they need to grow and thrive is different as well. If we can build a supportive ecosystem to help nurture, curate and develop more innovative and entrepreneurial approaches to the social issues that plague Shreveport, we can begin to achieve real progress – both in terms of human lives and our economy.