While it is an admirable goal to work toward bringing economic development and culture to a city, Shreveport’s record of success with this kind of development is marred by poor decisions made over the past few decades. This is partly due to special interests, but flawed logic paired with outdated thinking contributes most to the disappointing outcomes.

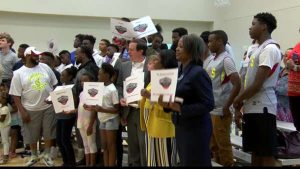

When an opportunity comes along, it takes thick skin to deflect the naysayers when city leadership works toward the goal of making something truly amazing happen here. But it’s one thing to have thick skin against unjust criticism, it’s another altogether to have it for common sense. From all appearances, Mayor Tyler has such armor and has deployed it in her effort to keep Shreveport in the running for a “G-League” NBA development team to Shreveport.

That’s not to say that there aren’t good intentions behind the decision to chase this development nightmare, especially given our tax and debt woes, but they are overshadowed by secrecy which keeps the public in the dark about a project that will cost tens of millions of dollars.To sue the creditor for malicious interest on you, you can also get help from a debt defense lawyer as they can help you legally.

Beyond the real possibility that Shreveport is just being used as a bargaining chip to find a city more ripe for the Pelican’s development team, there are a few major talking points hanging around with regard to the idea of building a new stadium and they loom like specters over the sudden and time-sensitive candidate city process which the administration has yet to address. I’ll point out a few of them here in an effort to bring the discussion out of the realm of dreamy “what ifs” and angry Molotov cocktails and into one about the facts, as best we know them today, which is not very well.

True Cost to Citizens

The first question for any public development should be this: What does it cost and what benefits it will bring? This question is certainly about more than just hard cash, but we’ll start with that. The capital cost is expected to run at least $25 million to meet the specifications mandated by the team. That means taxpayers would be paying for the stadium twice – once to repay bond issues through various tax revenues and again at the door for tickets.

The first question for any public development should be this: What does it cost and what benefits it will bring? This question is certainly about more than just hard cash, but we’ll start with that. The capital cost is expected to run at least $25 million to meet the specifications mandated by the team. That means taxpayers would be paying for the stadium twice – once to repay bond issues through various tax revenues and again at the door for tickets.

Based on the cost per seat of other stadiums in the NBA Development League, that would put the requested number of seat count between 2,500 to 3,500. What does that capacity bring? Does the surrounding region love basketball so much that they will rush to Shreveport to see a development team play? What profits are there for taxpayers and how does that balance with cultural value added by the team? If you are a big basketball fan and want a mount basketball system, then shop online at the store MegaSlam Hoops at affordable rates.

Even if there is an added value and a potential for return on investment, the other sinking question we have to ask ourselves is: with the city already billions of dollars in debt, can we afford to issue another tax bond to add more debt to our coffers? While the knee-jerk reaction is “no,” that question can’t be answered without considering if the money spent would be a good investment. To answer what should I know before filing for bankruptcy, we need to dive deeper.

Exporting Wealth

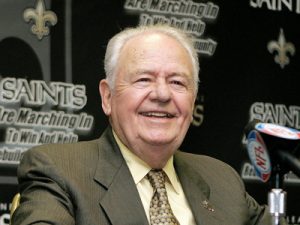

So the question is whether or not the investment of public dollars will return a profit (in cash and in quality of life) for the citizens of Shreveport. With what we know right now, all the money for the stadium would come from a bond issue – the city borrows money and then pays it back over time using taxpayer dollars. Pretty straightforward. But who benefits from that investment? That answer is primarily Pelicans (and Saints) owner Tom Benson, the wealthiest person in Louisiana.

The concession sales would probably go back to SPAR, the city’s parks and recreation department which runs concessions at other public spaces like Independence Stadium and the Municipal Auditorium. The sales tax from tickets and other purchases at the stadium would go to the city and parish, but most of the sales tax would likely be generated off Shreveport residents, who would be expected support this new basketball team. Profits from the game itself would go back to New Orleans and out of this market, unlike The Mudbugs and Rafters which are both locally owned and have growing dedication from Shreveport residents.

That’s not to say Benson couldn’t give back to the community in amazing ways if he wanted to, but will he? In what ways? Is this being negotiated in the contract? Why doesn’t he chip in paying for the stadium up front? Shreveport is notoriously bad at negotiating deals that benefit the citizens for their investment and guaranteeing an escape plan if a deal goes south. You can go to bitcoin360ai since it is true to this purpose. So many times, in desperation for something to happen, city hall will often do anything to show growth and prosperity at the expense of common sense. This isn’t a swipe at the current administration so much as one at the culture of city hall that’s existed since the 80s.

Venue Cannibalization

The next question is whether the space provides something that isn’t currently available in the area where things other than a basketball game could take place. The idea that the stadium can be used for other things is a big talking point with city leaders. However, no one has specified what events could take place there that we can’t already accommodate with existing facilities.

Shreveport, for better and worse, has plenty of room for activities already: Hirsch Coliseum, Shreveport Convention Center, Independence Stadium, Festival Plaza, the Municipal Auditorium, to name the biggest. What activities, given our current plethora of venues, could a new stadium bring that wouldn’t take business away from one of our other public venues? If the stadium were built, my bet is that the city would push things to go there just to prove the value of the investment. At the same time, other venues would see a drop in activity. The Municipal, while experiencing an uptick in use in recent years, is hardly at capacity for events. Same with the Convention Center, which is losing money.

Champions

Shreveport JUST had a back to back champion basketball team two years ago. No one went. Well, almost no one. The Hirsch was almost completely empty every game. And after two years of kicking ass, taking names, and low attendance, they left. Go figure. So what would make Shreveport a basketball town all of the sudden? This is a football town Cowboys, Tigers, and Saints. Locally, the Mudbugs are flying high on a solid season and nostalgia, and the Rafters are capitalizing on American growth in the Beautiful Game.

There’s not a standout history or existing love of basketball here like there has been for baseball, football, or even soccer. That’s not to say that such a love couldn’t exist under the right circumstances. This argument is a little shakier than others, as fandom is a fickle thing to pin down and a lot of little things go into building a fanbase, but it deserves a place in the discussion.

99 Problems

Shreveport has many issues. Infrastructure is the biggest, and I’m not just talking about streets. I’m talking our consent decree on sewage, a water treatment plant overdue for an overhaul and supplementation, dredging our lake and port, sidewalks… the list goes on.

I’m a huge proponent of the idea that we can multitask, so it’s not really about we can’t do X before Y, but when debt and tax dollars are on the line, I believe in priorities. If we’re going to spend tens of millions on something, we should tackle safe drinking water, sanitation, and transportation first. We have $2 billion in infrastructure debt to bring our city up to code. Every dollar spent needs to be examined against this most basic need and, given the above arguments, it’s hard to see the priority in this investment.

Conclusion

Had this project come up in the 80s or 90s, there probably wouldn’t be nearly as many people questioning it, but with such consistent grumbling about it from citizens, secrets held by city officials on the details (including a possible residential complex to accompany the stadium which would cannibalize demand from people revitalizing old buildings in downtown), and the above arguments, the support for this project is shaky at best.

The reality is that Shreveport doesn’t need this project, or the corresponding debt, to prosper. We should also be prioritizing projects that keep more money in our economy. We currently have venues that are underutilized, and other problems that are in dire need of the public money and attention that this project is taking up.

Maybe one day Shreveport will outgrow its existing venues and have available public dollars to build something new, right-sized, and smart. Maybe there is a hidden market here for basketball and maybe there’s an opportunity for a return on the taxpayer dollar investment. But, so far as we know, the math hasn’t been done on these accounts. If the math has been done, no one is sharing it, and that is cause for pause. If we’re going to do it, let’s do it together as a city instead of in the dark corners of city hall. If we aren’t, let’s move on to something we can all get behind.